My second job was hoeing sugar beets with my Mexican neighbors up in the fertile Red River Valley. We joined a migrant clan at a farm near Argyle for stints of both thinning and weeding. I'd walk over to the Gamboa's at 5 a.m. and we'd pack into their Oldsmobile and drive the 45 minutes in the dark, with loud Tejanas music blaring out of the back speakers. My only tool for that job was a hoe. We got paid $4.00 a row. Each row was a mile long. Big Joe Gamboa told me to thin out every third seedling. My first day I walked the row slowly, like a pastor in thought, counting 1, step, 2 step, 3 hoe. 1 step, 2 step, 3 hoe. I'd prick out that third plant with the corner of my hoe. The migrant workers, the families making their living by circling the country in time for the various cropwork--first California and the vegetable farms, then the Plains for the sugar beets, next the Midland, finally the south and all its fruit--all zipped through the rows like this: ba ding, ba ding, ba ding, ba ba ding, so that when I looked up from my careful counting most of them had worked their way nearly to the end of the rows. They were hoping to store up their winter wages on this route; I was hoping to get a new bike.

My first payroll job was as a car hop for the local A&W drive-in on Gateway Drive in Grand Forks. They gave me a uniform, an apron, and a coin changer I wore around my hips. They also gave me a warning that the first dropped tray was on them; any after that and the breakage that resulted came out of our paychecks. They thought this penalty would teach us to slide the auto trays correctly onto the half-open car windows. But that didn't prevent breakage. They seemed to forget about all the dolty drivers who knocked over those frosty mugs in a rush to pacify the people in the back seats. Each of those heavy mugs cost us 90 cents a crack.

My first salaried job was as production assistant for the college textbook division of West Publishing. I would assist senior editors and others in producing mostly entry-level books for the college market: criminology texts, and editions for human nutrition, organic chemistry, oceanology, astronomy. They gave me lots of tools, some familiar, some not.

Seemed like half the West Publishing staff, especially those assigned to the more profitable and historic law divisions, were women who sorted, counted, proofed, and corrected the millions of sheets of paper that passed through that institution each year. These women were paid a fraction of what the male managers and executives in the company were paid, and they worked in large pools set up on each floor. Once I saw a flyer on one of their bulletin boards: "If you take 0 sick days, you will get a raise. If you take 1-3 sick days, you may get a raise. If you take more than 3 sick days, you will not get a raise." And also once, "Women should not take handbags to the ladies' room, unless it is your lunch break."

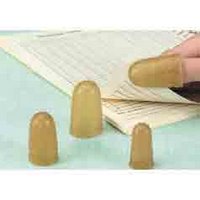

I was buffered from the patriarchy some by my status as a college graduate in the upstart and independent College Division. But I felt a solidarity with my sister word handlers. I noticed that they ignored the handbag warnings. I also noticed that they almost always left a rubber finger or two on the countertops of the bathroom sinks. I wasn't completely sure these weren't new contraceptive devices; women leave the strangest things in the powder room. After I asked about them, I got a nice stack of my own along with a pica ruler, a pack of pink gummy slips, and a bottle of Euricen from our department's Penta typesetting coordinator. I felt like I was heading for training in the lab at the Free Clinic.

No comments:

Post a Comment